Spending more time indoors gives me plenty of opportunities to cogitate, and during such an event I decided to look into the whole languages thing and their use in fantasy fiction of all kinds. For the most part, due to the fact the majority of people read or view in their native tongue, the language used must be understandable by the consumer. But sometimes the creators of such things want to evoke an authentic atmosphere, and thus need the characters to speak their own language. This is something of a problem because those languages don’t exist. So, how do they solve it? Sit back, relax, and I will explain.

The Don’t Bother Approach

Sometimes, writers just want to get on with the action and don’t want to mess about with the whole language thing. So, everyone speaks English (I make no excuse for English speakers here, most of us assume the same thing when we travel.) Everyone and everything, from pixie to giant, talking plants to creatures who have no mouth or lungs with which to produce speech, all fluent in English. I’m sure this happens in other languages as well, but I’m speaking from personal knowledge here.

The Make It Up As You Go Approach

Whether you’re writing for a film, a comic, a novel, or something else, this method involves simply making up words and sounds as you go along and hoping no one notices. This is the quickest and easiest method but sounds the least convincing and is likely to result in people complaining. Some will say it sounds like nonsense, and they’d be right, and some will say ‘I thought skweeboj was some kind of soup?’ It’s easier not to make such mistakes if you take notes of what your character meant when he said ‘skweeboj dodno tryttish!’ and next time you can use the same words again. (FYI, it means ‘You dishonour my soup!’ (or was it ‘…name!’? Should have written it down.))

The Just Enough Approach

This method is used extensively in films and is a sort of hybrid or compromise version of a fantasy language. When we first meet the madeupcountrians/ dwarves/ speaking camels they speak in their own language, with subtitles or some form of translation. After a few sentences, they switch to the native language of the film, the viewer assuming they’re still speaking their own tongue. This shows us the speakers have their own culture, but it saves time and money on inventing thousands of words and writing subtitles. Now, this is slightly more believable than the first method, but it can be confusing if there are humans in the scene, and it seems they can’t understand what’s being said. This is probably the one to use for most writers, it takes less time, is believable for the most part, and is usually more than enough for the scope of the story you’re creating.

The Extensive Conversations Approach

A more expanded version of the previous method, here the writer always has the characters speaking their own language, but everything they say is all there is. Each word and phrase is used correctly and consistently, but there’s no more, it isn’t a complete language by any means. This does take more time and effort but is the most believable without going over the top. The one drawback to this method is to make the language consistent without making it sound like English with the words replaced by made-up words. Not all languages have the same sentence structure and rhythm. For instance, the French ‘le souffle du dragon’ transposed into English would be ‘the breath of dragon’ but translated it would be ‘the dragon’s breath.’ The same meaning but different sentence structure. Now imagine a language spoken by a giant blue toadstool.

The Little-Known Foreign Language Approach

To avoid the time and effort required to invent an entire language, some writers use a pre-existing language, but one that’s obscure and not well known in the territory it’s being sold in. For instance, using a little-known language from Australasia in the western hemisphere. This has its drawbacks, of course, in that this is a small world, and the creative work in question could easily reach the ears of a native speaker and cause much amusement. (Dad, that ogre sounds like Grandma!) This language will probably have a written version as well, which also saves time, but with the same inherent problems. It also requires you to find someone who can write and speak that language, which could be something of a task all of its own.

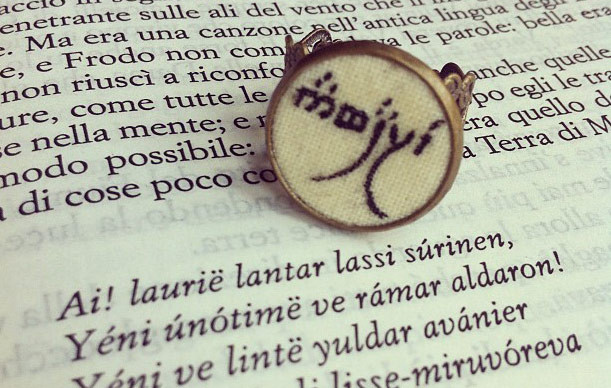

The Just Go For It Approach

We could also call this section the J.R.R. Tolkien approach. He invented not one but two whole languages, Sindarin and Quenya, and many more almost complete ones, including the written versions. Ok, he was a language professor, and so had a bit of an advantage, but it does show what’s possible if you’re prepared to put the work in. There are people on this Earth right now who speak these elven languages, who took the time to learn them. That’s how much of an effect fantasy literature can have on people.

To sum up, I would say those creating fantasy fiction should use whichever approach works for them and the material. I doubt many writers will need to invent a whole language, but it’s nice to know it’s possible if necessary.

Thank you for taking the time to read my semi-random thoughts. Until next time, hantanyel ar mára mesta!